Sudan

1) Short summary (one paragraph)

Sudan’s modern history is shaped by overlapping political, ethnic, regional and religious tensions. Oppression has taken many forms: colonial and post-colonial centralization and Islamization policies, large-scale counterinsurgency campaigns (most notoriously Darfur from 2003), authoritarian rule under Omar al-Bashir with repression of political opponents, and — since 2023 — a deadly factional war between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) that has produced mass displacement, famine, and continuing rights violations. International justice efforts (ICC warrants) and repeated humanitarian warnings have documented mass atrocities, but accountability and durable protection have been limited. Human Rights Watch+2International Criminal Court+2

2) Historical background — key phases

Pre-colonial & Ottoman-Egyptian era (up to late 19th century)

Sudan was a frontier space of diverse kingdoms and groups (Arabized northern groups, many Nilotic and other African groups further south and west). Religious identities were mixed and fluid; Islam spread gradually in the Nile valley, but the social map was complex rather than simply “Muslim vs non-Muslim.”

Mahdist period and Anglo-Egyptian Condominium (late 19th — mid 20th c.)

The Mahdist state (1880s) was an Islamic revolutionary regime that reshaped religious and political authority. Under the British-Egyptian condominium (1899–1956), colonial governance privileged certain northern elites and created administrative boundaries and policies (including missionary work in the south) that later hardened identity cleavages. These colonial arrangements set up political and cultural marginalization of southern and western populations. MERIP

Independence and the North–South conflicts (1956–2005)

After independence (1956) the Sudanese state pursued policies of centralization, Arabization and Islamization at different times. Tensions between a largely Arabized, Islamic north and largely Christian/animist south escalated into long civil wars (first and second Sudanese civil wars). These conflicts had strong religious and cultural dimensions; state policies and military counterinsurgency often targeted populations perceived as “other.” The south’s secession in 2011 (South Sudan) is a direct legacy of those struggles. Middle East Forum+1

Darfur and the early 2000s (2003 onward)

A turning point for international attention was Darfur (western Sudan), where a rebellion by marginalized groups in 2003 was met by a brutal counterinsurgency in which government forces and allied militias (the Janjaweed) carried out mass killings, sexual violence, village destruction and forced displacement. Human rights bodies characterized parts of the campaign as crimes against humanity and the ICC later issued arrest warrants for then-President Omar al-Bashir. Hundreds of thousands were killed and millions displaced. Although many Darfuris are Muslim, the violence targeted non-Arab ethnic groups and was framed in ethnic, not purely theological, terms. Amnesty International+1

Authoritarian Islamist rule (1989–2019)

Omar al-Bashir’s regime (from 1989) combined personalist military rule with alliances with Islamist political currents and imposed Islamic-oriented laws and policies. The state used security services to crush dissent, prosecute political opponents, and wage campaigns in the peripheries (South Kordofan, Blue Nile, Darfur). International criminal investigations (ICC) documented mass crimes under his rule. At the same time, the regime’s Islamization policies often affected minorities and dissenters, and political Islam became associated with state coercion for many Sudanese. Encyclopedia Britannica+1

2019 uprising and failed democratic transition (2019–2021)

Large popular protests starting in late 2018 over economic hardship led to Bashir’s ouster in April 2019. A fragile transition (civilian-military power-sharing) followed, but the period saw continuing rights abuses, a violent crackdown (e.g., the June 2019 Khartoum massacre), and eventual military takeovers (coup in October 2021). The transition failed to fully deliver justice or security for displaced and marginalized groups. ICNC+1

2023–present: SAF vs RSF and collapse of protection

In April 2023 fighting broke out between SAF and the RSF (a powerful paramilitary rooted in earlier formations including the Janjaweed). The fighting quickly spread; cities were besieged, hospitals and aid convoys attacked, and millions of civilians were forced from their homes. The conflict has produced what the UN and human rights groups call one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises — mass displacement, famine in some camps, and allegations of war crimes, ethnic targeting and sexual violence. Control of regions (notably Darfur) is contested and armed groups and tribal militias have multiplied. Human Rights Office+1

3) How “oppression” has worked in Sudan — patterns and mechanisms

State policies of marginalization and forced assimilation — central governments have at times pursued Arabization/Islamization policies (legal and cultural) that marginalized non-Arab, non-Islamic or regionally distinct communities in language, land rights and political power. These policies fueled rebellion and state repression. MERIP

Militarized counter-insurgency and paramilitary proxies — the Sudanese state frequently outsourced repression to militias (e.g., Janjaweed → RSF), enabling mass atrocities with plausible deniability; this pattern produced large-scale destruction and displacement, as in Darfur. Human Rights Watch+1

Legal and social restrictions under authoritarian rule — during Bashir’s era, laws and policing restricted civil liberties, targeted political opponents and sometimes imposed religious-moral regulations; this created coercive pressure on minorities and political dissenters. Encyclopedia Britannica

Ethnic and local violence with religious overlay — many attacks have an ethnic core (Arab vs non-Arab identity in Darfur, tribal disputes) that overlaps with religious identity — some victims are Muslim communities (e.g., many Darfur groups are Muslim) while others are non-Muslims; religious labels have sometimes been used politically rather than being the only driver. Human Rights Watch+1

Humanitarian access denial and economic marginalization — sieges, looting, and restrictions on aid delivery have produced famine, disease and displacement that disproportionately affect marginalized populations. The 2023-onward conflict made this dramatically worse. OCHA+1

4) Human impact — scale and examples (sourced facts)

Darfur (2003 onward): hundreds of thousands killed (widely cited estimates vary) and up to ~3 million displaced in the peak years; massive village destruction, sexual violence and long-term displacement into camps in Chad and within Darfur. Amnesty International

ICC action: arrest warrants for Omar al-Bashir (2009, 2010) for war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide related to Darfur; other Sudanese suspects have faced ICC proceedings. International Criminal Court+1

Current displacement and famine risk: since April 2023 the conflict has generated many millions of internally displaced people (UN/OCHA and UNHCR tracking shows numbers in the multi-millions; some sources report over 8 million displaced since 2023 and humanitarian agencies warn of famine in parts of Darfur). UNHCR Data Portal+1

Attacks on civilians and aid workers: documented attacks on hospitals, ambulances and humanitarian convoys — hampering relief and increasing mortality. Human Rights Office

(Those are some of the most load-bearing, well-documented facts about scale and accountability.) Human Rights Watch+1

5) International and legal responses

Human rights investigations by Amnesty, Human Rights Watch and UN bodies have repeatedly documented abuses and urged accountability. Amnesty International+1

International Criminal Court: warrants and prosecutions (Al-Bashir warrants; other Darfur defendants tried/convicted at the ICC or national courts in some cases). These mechanisms signal accountability but are slow and face political obstacles. International Criminal Court+1

Diplomacy & humanitarian aid: UN, regional actors and donor states provide relief and mediation, but access constraints, arms flows and regional rivalries complicate solutions. Recent diplomacy (e.g., proposals by regional powers and the “Quad” in 2025) aims for an interim truce and roadmaps for transition. Reuters

6) Present situation (as of latest reporting in 2024–2025)

The SAF–RSF war has escalated into a prolonged, multi-front conflict with severe civilian suffering: mass displacement (the world’s largest IDP crisis in recent reporting), attacks on towns, looting of aid, and famine in some camps. Parties and allied militias are accused of war crimes. International actors are pushing ceasefire and transitional roadmaps, but implementation is fragile. Reports since 2023 emphasize growing militarization (including reports of drones, foreign mercenaries and arms transfers) that risk widening the conflict. Human Rights Watch+2Reuters+2

7) Future prospects — scenarios and what will shape outcomes

A. Continued fragmentation and humanitarian catastrophe (high risk if current dynamics persist)

If the SAF–RSF fight continues, especially with external support and increasing weaponry (drones, mercenaries), we can expect prolonged displacement, more famine episodes, erosion of state institutions, and cyclical local ethnicized violence (not limited to religious communities). Reconstruction and accountability would be much harder. Human Rights Watch+1

B. Negotiated truce → fragile transition (medium chance with strong external pressure)

Regional diplomacy (Egypt, Saudi, UAE, US) and UN pressure can help produce ceasefires and short transitions toward civilian governance. Roadmaps proposed in 2025 aim for humanitarian pauses then political transition—success depends on enforcement, monitoring and willingness from combatants to disarm. If successful, this could reduce immediate suffering and open space for justice and rebuilding. Reuters

C. Fragmented local settlements with weak central authority

A possible outcome is decentralization de facto: local powerholders, tribal militias and RSF or other groups control territory; central state remains weak. This could relieve some local grievances but also create long-term insecurity, predatory local rule, and uneven application of rights. Amnesty International

Factors that will determine which path occurs

Regional geopolitics and external patronage (who supplies arms, funding, political cover). Financial Times

Ability of humanitarian actors to reach vulnerable populations and prevent famine. OCHA

Domestic political will for compromise and accountability, and the presence of credible transitional mechanisms. ICNC

Climate and economic stress (desertification, competition over pastoral lands) that fuel local conflicts. Minority Rights Group

8) What would reduce oppression and protect vulnerable communities (practical measures)

Immediate, enforceable humanitarian pauses and protected aid corridors to prevent starvation. Reuters

Arms embargo enforcement and curbs on foreign mercenaries and drone supplies. Reuters+1

Accountability steps: credible investigations, prosecutions (national or ICC), and truth-seeking to deter repeat atrocities. Human Rights Watch

Inclusive political settlement that addresses regional marginalization (land, local governance, resource sharing) and rebuilds public services. ICNC

Long-term development investments, climate adaptation and reconciliation programs for communities in Darfur, Kordofan and other affected regions. Minority Rights Group

9) Caveats and limits of this summary

Sudan’s situation is rapidly changing; specific battlefield control, displacement numbers and diplomatic moves can change quickly. I’ve cited major, reputable sources (UN, HRW, Amnesty, ICC, Reuters/Al Jazeera) for the core claims above. If you want, I can fetch the very latest situation reports for a particular month or region (for example: Darfur, Khartoum, Port Sudan) and provide a more granular timeline and data table. Human Rights Office+1

Khilafat

Join us in reviving the Khilafat.

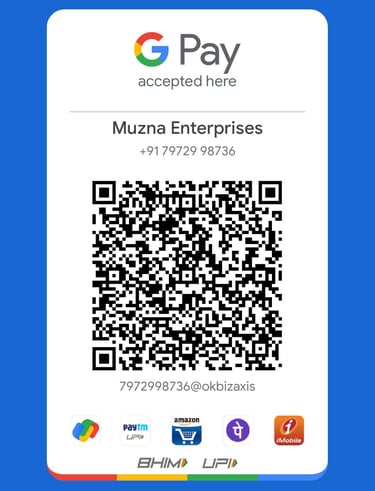

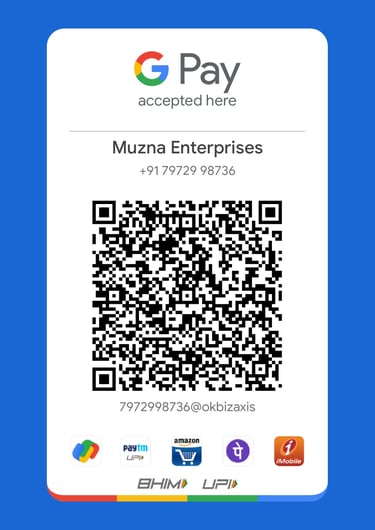

rizwan@muznagroup.com

+91-7972998736

© 2025. All rights reserved.