Rohingya Crisis

1) Who are the Rohingya and why this crisis?

- Ethnic and religious identity: The Rohingya are a predominantly Muslim minority who have lived for generations in Rakhine (Arakan) State, in western Myanmar. They have long claimed historical ties to the region, dating back centuries, but the Myanmar state rejects their claim to full nationality.

- Citizenship and statelessness: Myanmar’s 1982 Citizenship Law effectively excludes many Rohingya from citizenship, labeling them as “foreigners” or “non-citizens.” That law, coupled with state policies and mistrust, has left hundreds of thousands stateless.

- Core grievances: Denial of citizenship, restricted freedom of movement, limited access to education and healthcare, forced relocations, and systemic discrimination have made daily life precarious for Rohingya both inside Myanmar and in exile.

2) A concise timeline from the start of the crisis to today

- Pre-1948 to post-independence era (British rule to early independence):

- Rohingya communities have long existed in Arakan/Rakhine. The transition to independence in 1948 brought ethnic tensions to the fore in various forms, including disputes over citizenship and land.

- The 1942-era violence and displacement left lasting scars and complicated identities in the region. Some Rohingya suffered during wartime upheavals; others remained in Myanmar after independence.

- 1982 Citizenship law and statelessness deepens:

- Myanmar’s 1982 law effectively excludes many Rohingya from citizenship. This formalized statelessness for a large portion of Rohingya and restricted their civil and political rights.

- 2012 Rakhine State violence and displacement:

- A burst of communal violence between Buddhist and Muslim communities in Rakhine led to mass displacements, destruction of villages, and a climate of fear.

- Tens of thousands were displaced within Myanmar; many Rohingya fled to camps and other parts of the country. Humanitarian access was limited, making relief difficult.

- 2014–2016: Escalating ethnic discontent and new waves of displacement:

- The situation remained volatile. Restrictions and discriminatory policies continued, and some Rohingya sought routes to neighboring countries (often by boat) to escape persecution and poverty.

- 2017: The major refugee exodus and international focus

- Late August 2017: Military and security operations in Rakhine State intensified after attacks on police posts by an extremist group (the ARSA). The Myanmar army launched a widespread crackdown.

- Numbers and impact: Estimates vary, but around 700,000–900,000 Rohingya fled to neighboring Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar region and other areas, joining thousands who had already fled earlier years.

- Human impact: Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, UN investigators, and a wide chorus of observers documented mass killings, gang rapes, arson, and the burning of villages. The violence generated one of the fastest large-scale refugee crises in recent memory.

- Global response: International condemnation, calls for accountability, and debates over whether genocide was occurring. The UN and various governments called for investigations and safe, voluntary, dignified repatriation when feasible.

- 2018–2019: Repatriation attempts and humanitarian stabilization

- Bangladesh and Myanmar signed agreements to repatriate Rohingya refugees. The first returns began in 2018, but conditions in Myanmar were reported as unsafe (lack of citizenship, ongoing restrictions, and inadequate security guarantees).

- Very few Rohingya agreed or were able to return, and many who did leave again or refused to move.

- Inside camps in Cox’s Bazar and other border areas, humanitarian aid continued but faced funding shortfalls and logistics challenges.

- 2019–2020: Legal accountability channels open or proposed

- International legal avenues gained attention:

- The International Court of Justice (ICJ) case filed by The Gambia against Myanmar in 2019 alleging genocide against the Rohingya.

- In January 2020, the ICJ issued provisional measures ordering Myanmar to prevent genocide and protect Rohingya from genocidal acts, including preventing acts of violence, ensuring safe return of those who wish to return, and preserving evidence.

- Ongoing international diplomacy and sanctions discussions continued to push for accountability and safe conditions for refugees.

- 2020–2021: Coup in Myanmar and shifting dynamics

- February 2021: A military coup ousted the elected government, triggering mass protests and a brutal crackdown on dissent.

- The coup compounded the Rohingya’s precarious situation: in Rakhine and elsewhere, security dynamics shifted, humanitarian access was further restricted, and movements of displaced people remained tightly controlled.

- Rohingya in Myanmar (especially those who had remained in the country) faced renewed pressure, further restrictions, and limited prospects for durable solutions.

- 2021–2024: Ongoing displacement, climate risks, and a fragile humanitarian corridor

- In Bangladesh, the Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar continued to host roughly 1 million people, facing chronic funding gaps, vulnerability to floods and cyclones, and limited prospects for large-scale repatriation.

- The humanitarian response remained essential but constrained by funding, governance, and the broader political climate in both Myanmar and Bangladesh.

- The ICJ case continued through hearings about merits, with provisional measures in place since 2020 and ongoing discussions about accountability and future remedies.

- 2024–2025: The status quo and the search for durable solutions

- As of the mid-2020s, a large majority of Rohingya remained refugees in Bangladesh or displaced within Myanmar. They continued to lack citizenship in Myanmar and faced significant barriers to safe, voluntary repatriation and durable solutions.

- The international community continued to advocate for accountability for abuses, protection of civilians, and a pathway to safety, dignity, and eventual solutions for stateless Rohingya.

- The political and security dynamics in Myanmar, including the continuing governance crisis after the 2021 coup, complicated any potential resolution.

3) Core issues, dynamics, and actors

- Core issues

- Statelessness and citizenship rights: The core legal barrier is citizenship and the denial of political rights for Rohingya.

- Security and freedom of movement: Rohingya face restrictions on movement, access to education, healthcare, and livelihoods.

- Mass displacement and humanitarian needs: Millions have been affected across generations, with lasting needs in areas of shelter, food, water, sanitation, protection, and mental health.

- Accountability for abuses: The international community has pursued various avenues to establish accountability for alleged genocide, crimes against humanity, and ethnic cleansing.

- Key actors

- Myanmar government and military (Tatmadaw): Central political force in Myanmar’s governance and security policy; role in Rohingya restrictions, violence, and control over affected regions.

- Rohingya communities and refugees: Both those inside Myanmar and those in exile in Bangladesh and elsewhere who lobby for rights, safe return, and protection.

- Bangladesh government and humanitarian agencies: The primary host country for Rohingya refugees; responsible for camp management, refugee protection, and bilateral diplomacy with Myanmar.

- International organizations: UNHCR, IOM, OHCHR, and various NGOs leading humanitarian programs and advocacy; international courts (ICJ) assessing accountability.

- Donor governments and regional bodies: Countries and blocs who fund aid, apply sanctions, or engage in diplomacy (e.g., ASEAN dynamics, the EU, the United States, the United Kingdom, etc.).

4) Humanitarian situation on the ground (high-level)

- In Bangladesh (Cox’s Bazar and nearby camps):

- Population: Approximately 1 million Rohingya refugees in camps and host communities.

- Living conditions: Overcrowded camps with vulnerable settlements, flood and cyclone risks, limited livelihood opportunities, and ongoing health and education needs.

- Protection: Gender-based violence risks, child protection concerns, and the need for psychosocial support.

- Services: Ongoing aid for shelter, WASH (water, sanitation, hygiene), food, nutrition, and vaccination campaigns.

- Inside Myanmar, especially in Rakhine State:

- Displacement: Both long-standing internal displacement and episodic new displacements due to clashes and security restrictions.

- Rights and access: Severe limitations on movement, citizenship status, and access to services for Rohingya inside Myanmar.

- Global framing:

- The crisis is widely viewed as one of the most protracted humanitarian emergencies, with systemic policy-driven root causes—statelessness, discrimination, and lack of citizenship—compounded by ongoing conflict and governance instability.

5) Legal and accountability dimensions

- ICJ case: The Gambia v. Myanmar (genocide case)

- Filed 2019; ICJ issued provisional measures in 2020 demanding Myanmar prevent genocidal acts and protect Rohingya. The case probes whether alleged genocidal acts constitute crimes under international law and seeks remedies and accountability.

- As of 2024–2025, the case remains ongoing through merits hearings and related proceedings. The final merits decision was not delivered by 2024; outcomes are uncertain and depend on international judicial processes and Myanmar’s cooperation.

- Other accountability mechanisms

- UN investigations and expert panels have documented abuses and called for accountability.

- Some countries have imposed targeted sanctions or issued statements condemning the violence and urging human rights protections.

- Domestic accountability within Myanmar remains blocked by the political and security situation post-2021 coup.

6) Repatriation attempts and the path to durable solutions

- Repatriation attempts

- Post-2017, joint initiatives between Bangladesh and Myanmar aimed to return Rohingya to Myanmar with guarantees of safety and citizenship. In practice, returns have been extremely limited due to ongoing fears, lack of documentation, and absence of guaranteed rights in the country of origin.

- By the mid-2020s, only a tiny fraction of those who fled had consented to repatriation, and many who returned faced renewed displacement or forced relocation.

- Durable solutions framework

- The international community has emphasized three pillars: safe and voluntary repatriation when conditions permit; local integration where possible and safe (in places where Rohingya already reside, notably in Bangladesh); and resettlement to third countries (limited in number and logistics).

- The most feasible near-term approach remains humanitarian protection and support for refugees, ensuring basic needs, protection, and a pathway to citizenship or legal status, if and when the regional political context allows.

7) What has changed recently (2024–2025 snapshot)

- Political and security context in Myanmar remains unstable due to the 2021 coup and ongoing conflict, complicating any potential returns or reforms that would address Rohingya citizenship and rights.

- In Bangladesh, the Rohingya refugee situation persists as a protracted humanitarian crisis, with sustained aid needs, climate vulnerability (coastal and cyclone-prone environment), and limited durable solutions in sight.

- The ICJ process continues to provide a juridical path toward accountability and potential remedies, though the timeline for a final merits judgement is uncertain.

- The international community continues to advocate for protection, dignity, and a rights-based solution, balancing diplomatic engagement with humanitarian support and accountability mechanisms.

8) Why this crisis matters globally

- Statelessness and citizenship rights: The Rohingya crisis highlights how statelessness undercuts human rights and basic dignity, and it raises questions about national sovereignty, citizenship criteria, and minority protection.

- Humanitarian impact: It is a major displacement crisis with cross-border spillovers, affecting regional security, health, and climate resilience.

- Accountability and rule of law: The ICJ case and UN investigations test how international law can respond to alleged genocide and crimes against humanity when state actors are involved.

- Climate vulnerability: Rohingya refugees and displaced populations live in climate-sensitive environments; mitigating climate risks is essential to humanitarian planning.

9) Where to go for deeper reading and reliable data

- Core reports and statements

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR): Rohingya refugee stats, camp conditions, repatriation status, and country-by-country data.

- International Organization for Migration (IOM): displacement, health, shelter, and climate risk information for Rohingya populations.

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR): human-rights-focused reporting and findings on abuses.

- Human Rights Watch (HRW) and Amnesty International: in-depth investigations into violence, abuses, and accountability.

- The International Court of Justice (ICJ): case documents and provisional measures related to genocide allegations.

- Background and analysis

- The Gambia v. Myanmar (ICJ) case materials and subsequent hearings.

- Academic and policy analyses on statelessness, citizenship laws in Myanmar, and regional refugee governance.

- Reports on climate risk and refugee resilience in Cox’s Bazar.

- News and current affairs

- BBC, Reuters, AP, Al Jazeera, The Guardian, and The New York Times regularly cover updates on the Rohingya situation, repatriation attempts, and humanitarian needs.

- For Bangladesh and Myanmar governance contexts, look to national news and regional outlets for policy changes and humanitarian notices.

11) Final take

- The Rohingya crisis is sustained by a combination of legal statelessness, systemic discrimination, and protracted displacement, compounded by regional instability and climate risks.

- There is no simple solution in the short term. A durable resolution would require:

- Citizenship rights and legal recognition for Rohingya in Myanmar (or a sound, rights-respecting pathway).

- Safe, voluntary, and dignified repatriation only when conditions in Myanmar guarantee security and rights.

- Meaningful international accountability for abuses and a robust humanitarian response to shelter, health, and education needs.

- Long-term regional cooperation to address displacement, border management, and climate resilience.

Khilafat

Join us in reviving the Khilafat.

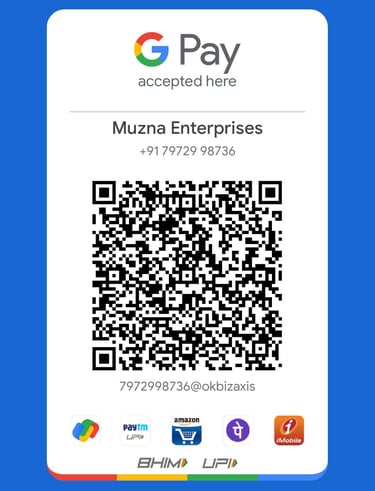

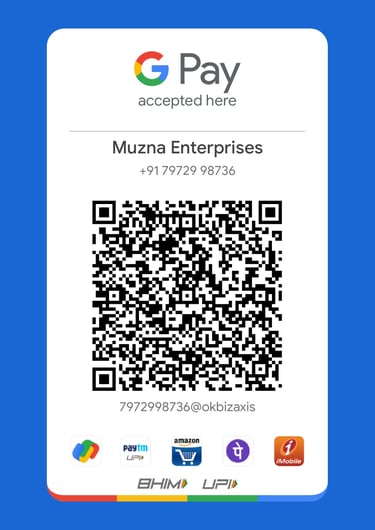

rizwan@muznagroup.com

+91-7972998736

© 2025. All rights reserved.